Language is an expression of culture and gives a connection to family, country and community.

Ninety two percent of Indigenous languages are fading or extinct. Australia has suffered the largest and most rapid known loss of languages and past government policies have been largely to blame.

This is clearly outlined in the Our Land: Our Languages report which was released by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs late last year.

The committee found governments had actively repressed the use of Indigenous languages throughout contemporary Australian history. They did so by outlawing the use by Aboriginal people of their mother tongue.

Australia’s first chair of endangered languages, Professor Ghil’ad Zuckermann from the University of Adelaide puts it bluntly. Those policies have resulted in “linguicide”.

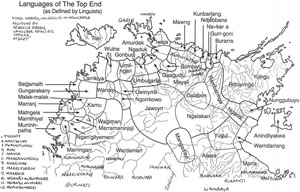

Zuckermann cited the 2005 National Indigenous Language Survey (NILS) Report to reinforce his point. It shows Australia was home to more than 250 distinct languages before European invasion.

Aboriginal people were typically multilingual. They were likely to speak as many as half a dozen languages, in addition to their own. Today, most of Australia’s Indigenous languages are no longer spoken fully or fluently.

As many as 50 languages can be expected to reach this stage of endangerment in the next 20 to 30 years, as the most severely and critically endangered languages lose their last speakers.

Of the original known languages, the NILS report found only 18 to be “safe/strong” in the sense of being spoken by all age groups. Just over 100 are still alive but highly endangered, spoken only by small groups of people mostly over 40 years of age.

Without decisive action, NILS reported, such languages are at risk of being lost in the next 10 to 30 years. The remainder are either no longer used or remain active as strong markers of country and identity. All continue to face uncertain futures and require ongoing action and support.

So what, you may ask, is so tragic about the loss of a language? Isn’t language just a tool for communication? Does it really matter what language is being spoken as long as people can communicate?

The simple answer is yes.

It matters on a personal, cultural and historical level. Language is far more than just a communication tool. It is a source of pride and strength.

It is an expression of culture and a way to keep the very essence of that culture alive. It goes to the heart and soul of one’s identity. It gives connection to family, country and community.

Language is a crucial and often missing part of the puzzle when it comes to tackling Indigenous disadvantage.

Research has shown Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who speak their language have markedly better physical and mental health, are more likely to be employed and to attend school, and are less likely to abuse alcohol or be charged by the police.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages also carry an intimate understanding of the ecological systems and the land with which they are associated.

Speaking in one’s native tongue forms a crucial component in unlocking and passing down knowledge from generation to generation. Many Australians fail to understand this.

This is not surprising. The 2011 Census revealed 81% of Australians aged five years and over speak only English at home.

The census found first-generation Australians had the highest proportion of people who spoke a language other than English at home (53%).

The rate was much lower for second generation Australians at 20% while the incidence for third or more generations dropped to an abysmal 1.6%.

It is a sad reality and a reflection on the repressive need to conform that parents often choose to speak English at home instead of their native tongue in their pursuit to become more “Australian” and to help their children fit in.

As a first generation Australian of Indian descent, my parents made the decision to abandon their use of Tamil and Hindi in an effort to help my brother and I “fit in.”

Almost 30 years later that decision remains a highly contested point of conversation and source of tension between us.

When I travelled through India in 2011 with my father I felt locked out of my culture and family.

I could not understand what priests were saying during temple ceremonies or the reasons behind my great grandmother’s tears when she spoke in Tamil about our family’s history.

“What did he say? What did she say?” I would continually ask.

“I’ll tell you later,” my father would reply. He never did. I eventually stopped asking.

On a recent trip to Fiji, a close family friend of my mother’s broke down as she spoke in Hindi about her personal experience during the 1987 military coup.

She explained where the latest coup fit in the context of Fiji’s historic volatile relations between the military and government and what it was like for Indians growing up in Fiji.

It was an opportunity to understand the significance of my mother’s decision to leave her homeland in search of a better life for her family. But over the course of two hours I was only able to decipher a few details.

Despite being able to speak English fluently, my mother’s friend felt more comfortable relaying her deeply personal account in Hindi.

When I asked my mother what was said all I received were the broad strokes. The finer details remain locked behind the mother tongue.

By Shyamla Eswaran

[This article was first published at Tracker.]

From GLW issue 992

https://www.greenleft.org.au/node/55550

Saturday, December 7, 2013

languagelandscape.org.

languagelandscape.org.

3

3