The world loses a language every two weeks

"When I speak language, it makes me feel home" - Roger Hart, elder and Cape York Guugu Yimithirr speaker

"Having a policy in place is essential to the survival of our people and languages. It would recognise our languages at a political level and ensure regular and consistent funds required to ensure Aboriginal languages experience growth and few impediments. Currently Australia does not have any list of any languages and as a result allows government to pay lip service to the promotion and funding of Aboriginal languages which is why we get sporadic funding allocations and little acknowledgement of our unique languages." - Lester Coyne, Former National Chair of the Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Languages.

Indigenous disadvantage is widely recognised in Australia. It is the source of numerous reports, parliamentary enquiries and countless unmet recommendations. More recently child abuse in indigenous communities have been in the political spotlight. The new government has responded by continuing to support the intervention in the Northern Territory and by making a formal apology on behalf of current and past parliaments to the stolen generations.

Indigenous languages are a crucial and often missing part of the puzzle of tackling Indigenous disadvantage. The current Prime Minister Kevin Rudd understands the importance of cultural diplomacy when talking to the Chinese but culture and language are rarely included in the strategies to improve social, economic, employment and health indicators for Indigenous communities.

Languages contain complex understandings of a person's culture, their identity and their connection with their land. Language enables the transference of culture and cultural knowledge across generations. Languages are a source of pride and strength.

Supporting languages can have flow on benefits into broader educational, employment and health outcomes. Languages are a key to unlocking indigenous disadvantage and crucial in the journey of reconciliation.

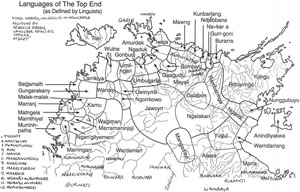

Australia was home to over 300 distinct languages. Each indigenous person was likely to speak at least 3 languages in addition to their own (L. Irabinna-Rigney, 2002). In the last 218 years Australia has suffered the largest and most rapid loss of languages in the world (Nettle and Romaine 2001:9). The percentage of Indigenous people speaking an Indigenous language decreased from 100% in 1880 to 13% in 1996, and in most cases this trend is worstening (McConvell and Thieberger, 2001).

Today, only 145 indigenous languages are still spoken in Australia, of which 110 are critically endangered (NILSR 2005: 24). A language is listed as critically endangered if there are only a few remaining speakers and no intergenerational language transition. While around 17 languages are not currently considered endangered, all indigenous languages face an uncertain future if immediate action and care are not taken.

Australian indigenous languages are considered globally endangered because of their uniqueness and the fact that they are spoken no-where else in the world.

"Indigenous activists argue that if our languages were like animals under threat of extinction there would be global outcry" - Lester Irabinna Rigney, Assoc. Professor, writing on Indigenous languages for 15 years (FATSIL Newsletter, March 2002, p. 9).

In Australia, there are examples of the decline in the speaking of Indigenous languages being arrested or reversed, and languages which were listed as critically endangered being brought back to life. In South Australia the Kaurna language was considered a dead, or 'sleeping', language. Now, thanks to the Kaurna Language Revitalisation Project, Kaurna is being spoken by increasing numbers of people. The Project also resulted in improved the awareness of Kaurna language and culture in the local non-Indigenous communities (7.30 Report, 28/2/2001).

Many projects like this one are being undertaken by local communities through Aboriginal Language Centres, schools and, occasionally, universities. The bulk of federal government funding for these maintenance and revitalisation projects comes from a section in the Commonwealth Department of Communication, Technology and the Arts.

Internationally, there are many examples of countries working on recognising, promoting and protecting their Indigenous languages. The UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ratified in 1976 states that

"... persons belonging to ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities shall not be denied the right... to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their religion, or to use their own language." (NILS 2005:33)

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples has not been ratified by Australia. It is stronger that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in its specific support for Indigenous language rights and the responsibilities this places in the hands of the state (IWGIA, 2007).

In New Zealand, the Maori Language Act 1987 established Maori as an official language of New Zealand, alongside English. The Act also established the Maori Language Commission which advises on government policy. The 1990 New Zealand Bill of Rights recognises Indigenous peoples' rights to language. These developments have resulted in policies and programs, including the Language Nests, that have greatly increased the numbers of Maori speakers across the generations (Kehonga Paper 2003).

The decades of the 1980's and 1990's in Australia saw an unprecedented interest in the preservation of Indigenous languages. The first time that the federal government acknowledged Indigenous Languages was in the 1987 Australian National Policy on Languages. It stimulated positive many developments including the funding of Regional Aboriginal Language Centres and languages trickled into schools across the country. Unfortunately this policy has been undermined by neglect and a shift back to monolingualism.

In the past 15 years Federal parliamentary committees have recognised the importance of protecting and promoting Indigenous languages and culture through the recommendations made in committee reports on Indigenous health, education, deaths in custody and violence. Despite this, there is currently no overall policy on Indigenous languages, no consistent approach to funding allocations or national body enabled to advise on policy development.

New South Wales is currently the only state in Australia that has a statewide 'Aboriginal Languages Policy', and Victoria is in the process of developing one.

There has been a lack of leadership at the federal level and significant opportunities to make a meaningful and effective contribution have been lost. With the right mix of community involvement, coordinated government support and innovative policy development Indigenous Australians can maintain and reclaim their languages and with them cultural and ecological knowledge of value to all Australians.

WHY PROTECT INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES?

"Language is important because it is a way to express identity and be proud of where they come from and who they are. If a person knows a word in their language he/she is maintaining a link that has lasted thousands of years, keeping words alive that have been used by their ancestors - language is an ancestral right and it distinguishes something special about Aboriginal people from non-Aboriginal people. Language is a part of culture, and knowledge about culture is a means of empowering people. Language contributes to the wellbeing of Aboriginal communities, strengthens ties between elders and young people and improves education in general for Indigenous people of all ages." - Victorian Aboriginal Centre for Languages

Culture - Language maintains the strength of a person's culture and identity. When a person has a strong connection to their own culture and language, it provides an additional channel for communication with that person and their community about issues such as education, health and employment.

Health, Education, Employment - By accessing communities and particularly the younger generations through culturally and linguistically appropriate approaches you will have greater success in getting the communities involvement and hopefully better outcomes in areas such as youth literacy, unemployment and the associated problems of crime and substance abuse. Indigenous language programs in schools have shown to have a positive impact on school attendance rates and community involvement in schools. More generally, learning a second language has proven improvements in cognitive development and in the literacy of both languages. Reconciliation - Supporting the reclamation and maintenance of Australia's Indigenous languages is an essential element of genuine reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Efforts to date represent real and meaningful attempts to overcome more than two centuries of dispossession. The results of this work are not only symbolically powerful but are crucial elements in improving the wellbeing, cultural and economic situation for Indigenous Australians.

Science and sustainability - Australian indigenous languages carry with them an intimate understanding of the ecological systems and the land from which they came. Losing these languages results in a loss of knowledge of species, behaviours, habitats, climatic patterns and sustainability practices that could lend support to tackling the increasing environmental challenges we face in Australia.

There are also potential macro and micro economic benefits from research into the ecological knowledge of Indigenous Australians, particularly looking into pharmaceutical properties and the ecologically sustainable agricultural development of Indigenous plant and animal species.

Economics - Languages can play a vital role in improving the economic prospects of Indigenous individuals and communities. Bilingual education has improved the numeracy and literacy of indigenous students. Strong languages can result in more opportunities for employment in areas such as education and training, translation and interpreting, and underdeveloped areas of cultural tourism.

Heritage - Australia's unique indigenous languages are a vital and vibrant part of Australian culture heritage. They represent a connection for many Indigenous communities to their pasts, an understanding of their cultures today, and provide a window for non-Indigenous Australians to appreciate the diversity, history and strength of the many cultures in their country.

NATIONAL INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE POLICY DIRECTIONS FOR AUSTRALIA

A National Indigenous Languages Policy can be another crucial step in the shift away from the politics of despair to the politics of hope.

The following recommendations are made on the basis that the detail is developed in close and sincere consultation with the relevant stake-holders within the Indigenous communities and relevant national bodies.

For this policy to be seen as sincere and genuinely geared towards implementation it is essential that time-frames are determined and commitments made to budgetary support for all of the following activities.

Immediate and practical priorities for action

? Establish a National Council on Indigenous Languages representing all stakeholders to make recommendations on a National Indigenous Languages Policy.

? Establish a National Indigenous Languages Centre - membership including Regional Aboriginal Language Centres, relevant National bodies - FATSIL, AIATSIS, community representatives, linguists – to advise government on policy direction. Other functions of the centre to be determined through the consultation process.

? Develop a whole of government approach with a National Indigenous Languages Policy that shifts the government into a position which supports and promotes Indigenous languages. The Policy could overcome current problems with inter-departmental policy coordination; improve needs assessments for allocating existing funding and to identify priorities for future funding opportunities.

? Establish a nationally coordinated approach to research and data cllection on Australian languages, including Creoles. To make targeted funding more effective it is essential that better data is collected – in coordination with national agencies including (but not limited to) AIATSIS, FATSIL, government departments and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. More research needs to be undertaken in trends across Australia as well as detailed regional studies.

? Establish a National Languages Database.

? Support the states and territories in the development of statewide language policies and indigenous language curricula in schools.

If you would like to comment on this document, please email Melanie Gillbank at the Ngapartji Ngapartji project on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Or contact Alex Kelly, Creative Producer of Ngapartji Ngapartji on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and 08 8953 5463

For more information visit Ngapartji Napartji www.ngapartji.org and BIG hART www.bighart.org

References and Further Reading

Vanishing Voices - The Extinction of the Worlds Languages, Nettle, D and Romaine, S, Oxford University Press, 2000 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005, Submitted to the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts by AIATSIS in association with the Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Languages (FATSIL) 'Lost for Words, The lonely fight to save our dying languages', Good Weekend, John van Tiggelen, Sept 10 2005, p. 25 'Bread Versus Freedom', FATSIL Newsletter Voice of the Land, Lester Irabinna-Rigney, March 2002, p. 9S State of Indigenous Languages in Australia 2001, N Thieberger and P McConvell, Department of Environment and Heritage, 2001 The Voice of the Land - Published by the Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Languages (FATSIL) also available on www.fatsil.org.au Maori Language Nests in NZ: Te Kohanga Reo, 1982 - 2003, Presented by Titoki Black, Phillip Marshall and Kathie Irwin) at the UN Forum on Indigenous Issues, New York, USA May 12 – 22, 2003 Aboriginal language resurrected in South Australia, 7.30 Report, ABC, 28/2/2001 Linguistic Rights - National Constitutions, MOST Clearing House, UNESCO, Accessed at

Speaking out for an Indigenous Australian Languages Act: the case for legislative activism for the maintenance of Australia's Indigenous languages, Crossings 2002 (Volume 7), Dr Christine Nicholls, Australian Studies, Flinders University. Accessed at Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Persons, International Working Group for Indigenous Affairs, Accessed at: Victorian Aboriginal Centre for Languages, homepage accessed at April 2007

Big hART's Ngapartji Ngapartji Briefing Document

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES IN AUSTRALIA

"The world loses a language every two weeks" - Wade Davis